Japanese water ladles, known as hishaku, are a common sight in Japan. Traditionally made of bamboo, you can find them at the entrance of shrines to cleanse your hands and mouth before entering (temizu), as well as being used as part of Japanese tea ceremony.

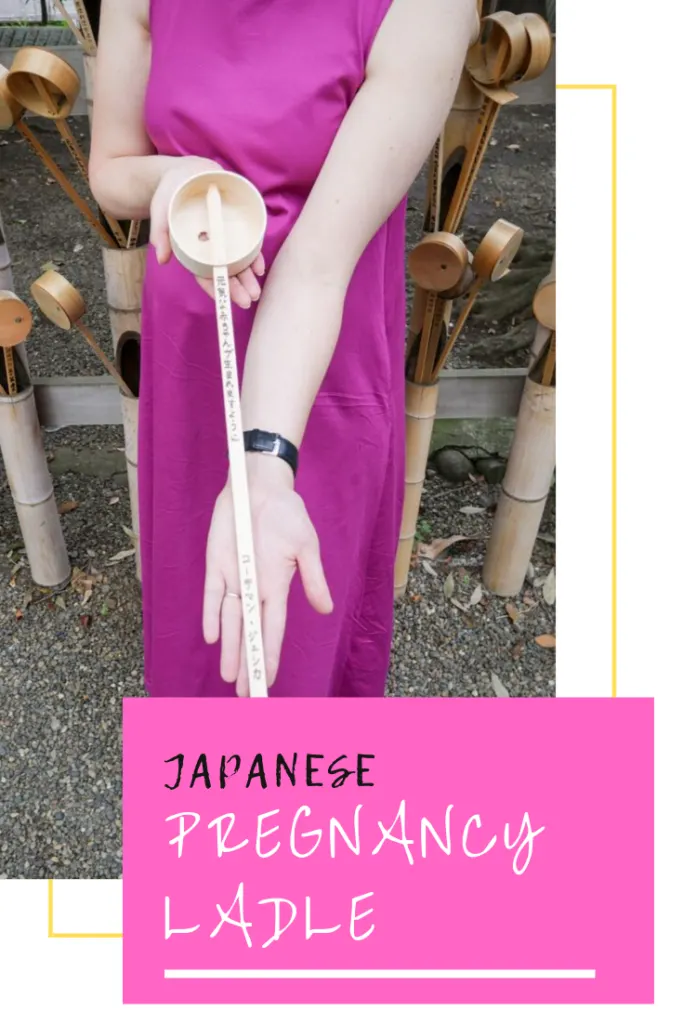

But one relatively unknown usage of Japanese water ladles is their role in pregnancy ritual. Basically, bottomless ladles or those with a hole punched through them can be used as a type of anzan kigan (安産祈願), safe birth prayer.

But how you ask?

Bottomless water ladles for a safe birth?

Yes, let me explain.

A regular ladle holds water but if there is a hole in it, water can pass through it easily.

Pregnant women therefore offer bottomless or punch-bottom ladles, known as sokonuke hishaku (底抜け柄杓), at shrines in the hope that their births will also be easy and free of complication.

Are punch-bottom hishaku common?

No, they are extremely rare, and in fact you’ll be hard pressed to find a Japanese person who has even heard of this ritual.

I learned of this practice when I visited Okunitama Shrine in an area of Tokyo called Fuchu, in which there is a small shrine called Miyanome Shrine on the grounds dedicated to women and childbirth where these ladles are offered.

I am unaware of any other shrine in Tokyo where this custom is practiced, however, there are a couple of examples of shrines in other parts of Japan where pregnant women offer these unique ladles for a safe childbirth.

One is Otonashi Shrine in Ito City along the Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka Prefecture and the other is Sangoji Shrine near Minobu, Yamanashi Prefecture, where the handles of bottomless ladles are pushed into the hillside surrounding a building which houses deities that watch over women during childbirth.

It is far more common for pregnant women to participate in other Japanese pregnancy rituals such as Inu no Hi (Day of the Dog) during the 5th month of pregnancy, or to simply visit a shrine to offer a prayer and buy a special amulet or a maternity belt, known as haraobi, to support their growing bellies.

How did this Japanese pregnancy ritual start?

While the idea behind the sokonuke hishaku makes sense, exactly how it came to be practiced in these select locations, and virtually nowhere else in the country, is shrouded in a little more mystery. But there are a couple of different stories and legends about the origin of this practice that might help explain.

According to local legend in Minobu, Yamanashi Prefecture, it is believed that a travelling monk was approached by an expecting couple having a difficult pregnancy and who were concerned about a safe delivery. He advised them to prepare a ladle with no bottom and when the couple was blessed with a healthy baby boy, they dedicated the ladle to the shrine. Over the centuries, local residents have been continuing this tradition by offering bottomless ladles for a safe birth.

As for Fuchu in Tokyo, Miyanome Shrine is where Minamoto no Yoritomo, the military commander who erected Japan’s first samurai government, prayed for his wife Masako Hojo to have a safe childbirth back in 1182. The link to the ladles is unclear, but perhaps we can assume the military commander had seen or heard of the practice elsewhere during his travels in Japan.

Offering a sokonuke hishaku in Tokyo

The unusual nature of the punch-bottom ladle just made me more eager to try it. So when I became pregnant, I returned to Miyanome Shrine at Okunitama Jinja in Fuchu, Tokyo, to show you what it’s all about.

You’ll actually pass Miyanome Shrine to your left before you enter the main shrine area. However, you’ll need to enter Okunitama Shrine proper to buy your ladle first. You’ll find the counter selling them and other amulets to the right of the main prayer hall.

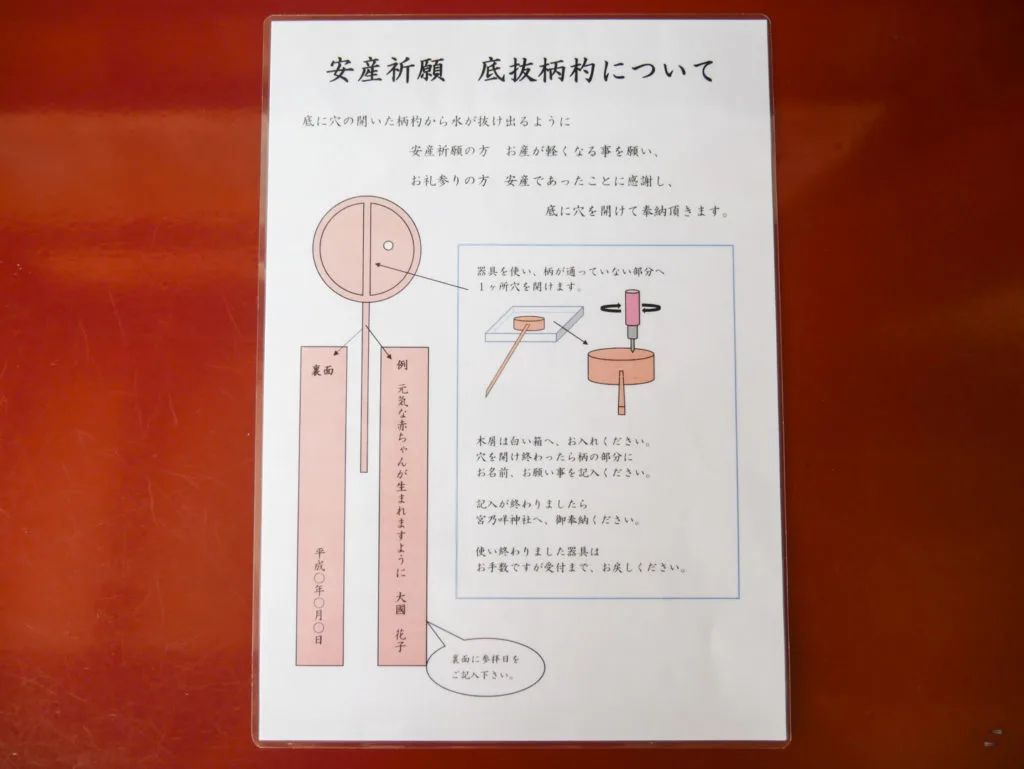

After purchasing your hishaku (1500 yen), you’ll also be handed an information sheet and a small box containing a tool to make the hole in your ladle and a marker to write on the handle.

While it may look complicated, it’s actually a simple process, so you needn’t worry if you are unable to read the instructions.

Essentially, all you have to do is write the date of your visit on the top side of the handle (that is, when the ladle is facing down). You’ll be able to see the name of the shrine already written on this side and you just write the date at the bottom. And on the other side, you write your wish at the top and your name at the bottom.

As for the tool, it’s simply a matter of applying pressure as you turn it until you have made a hole all the way through.

There is only one tool available, so be sure to pass it on to anyone else waiting once you’re done, or hand it back to the staff, along with the marker and instructions.

Then you can go back out to Miyanome Shrine to offer a prayer and place your ladle among the others.

And that’s it! You’ve successfully performed your special ‘sokonuke hishaku’ safe birth prayer.

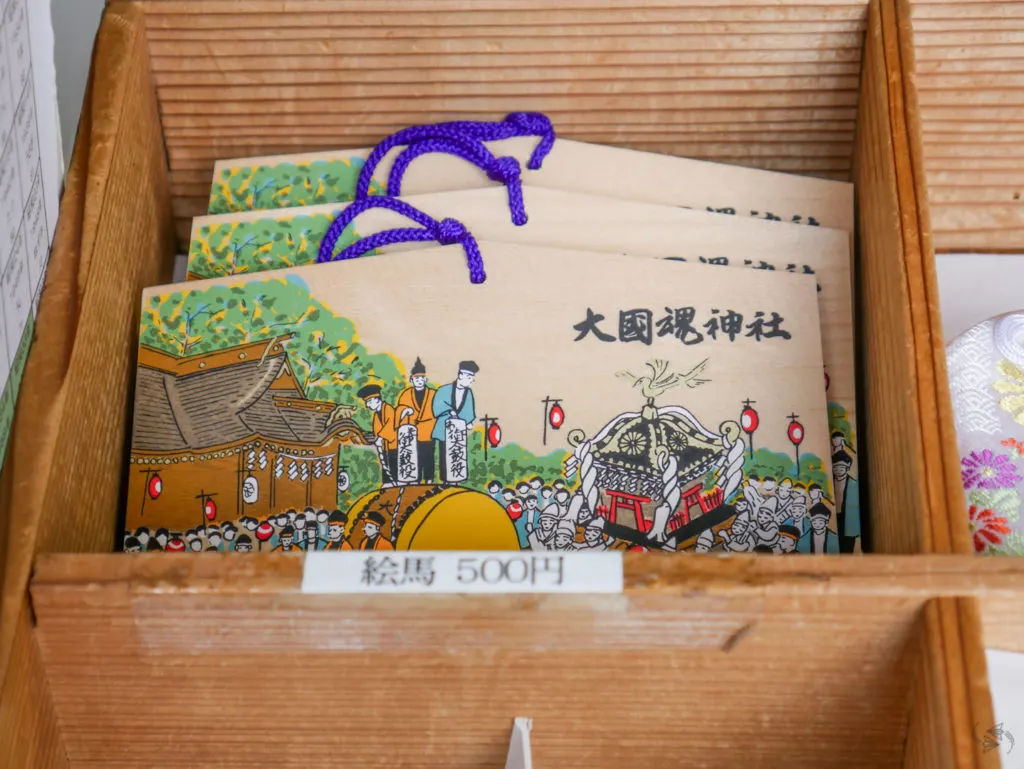

You may also notice ema, wooden plaques, that have been offered as well. They are common across Japan and most shrines will have a special design.

As writing your wish on the ladle and on an ema is essentially the same thing, there is no need to do both (and from my conversation with the shrine maidens it seems that no one really does).

But if you want to, or you’d prefer to write on a plaque instead, you can buy a shrine plaque for 500 yen from the same place as the ladles. This will be a generic plaque for the whole of Okunitama Shrine that is used for any type of wish. You’ll see them hanging within the inner grounds as well.

At the women’s shrine (Miyanome Shrine) where the ladles are placed, however, you’ll also see two other types of ema. One is of a woman knelt in prayer, while the other is the same with the addition of a baby in her arms. The former is one that is offered during pregnancy for a safe childbirth and the latter is offered after birth to express gratitude for a safe delivery.

Unlike the generic plaques, however, these ones are not available at the shrine and instead can only be bought at a stationery store by the name of Nakaman Honten (中万本店) in the Foris Building about halfway between Fuchu Station and Okunitama Shrine.

If you’re arriving at Fuchu Station and want to buy one, you should get one on your way to the shrine and bring your own marker (or pop over to the counter at Okunitama Shrine and ask to borrow one).

At the time of writing, the pregnancy ’ema’ were located in the far left corner of the store. With the plaques to your left, this is the view you should get inside the store.

They stock both types of pregnancy ’ema’ (pre-birth and post-birth) and cost 1500 yen each.

Do you have any special rituals for pregnancy in your culture/where you live? Tell me about them in the comments.

If you’re looking for more things to do in Fuchu, Tokyo, check out our video.

Alison and Don

Thursday 3rd of October 2019

This brought back some lovely memories. My first day ever in Japan I went with a guide (from Tokyo Free Guides) to Fuchu and to Okunitama Shrine, and happened to see a traditional wedding party there which was thrilling for me. I asked him to take me there because I wanted to make sure I knew how to get there from central Tokyo for the Kurayami Festival - and I then spent another 2 days at the shrine along with 700,000 other people at the festival. It was definitely one of the highlights of my visit. I love the ladle ritual for a safe and easy birth. The Japanese think of rituals for everything. You must be near your time now? Alison